The Woman (Doctor) Question and Nineteenth-Century Medical Journals

“The medical-women question is perennial. It knows no limits; we encounter it at every turn – at the universities and at the examining boards, at medical schools and in hospitals, in periodical literature and in works of fiction.”

(Lancet, 3 November 1877)

Of course, the readers of the Lancet were only too familiar with the ubiquity of the “medical-women question”, for it confronted them not only in their institutions and through popular culture, but in the pages of their medical journals as well. For the Lancet and its contemporaries were part of this wider debate over – or preoccupation with – the (im)propriety and (un)desirability of the female doctor: a new breed of practitioner who appeared on the British medical scene in the 1850s and 60s and had gained a foothold by the century’s close.

When I began working with the Royal College of Surgeons’ collection of Victorian medical journals – as part of my DPhil on the doctor/patient relationship in the nineteenth century – I was awestruck (and yes, perhaps a little intimidated too) by the sheer volume and scope of material on offer. I thought that by focusing on one subject – women doctors – as a point of departure, they would be easier to navigate. But I was unprepared for how much this one topic would dominate the columns of the period’s medical journals, from the long-running stalwarts with which we’re still familiar (such as the Lancet and the British Medical Journal) to lesser-known publications, such as the Medical Press and Circular and the Medical Mirror.

Nevertheless, tracing these debates has proved hugely illuminating, for it has revealed not only the varying and changing attitudes towards women doctors but much about working with historical medical journals as well.

One of the first lessons I learned was the incredible diversity of opinions they held, which challenged my simplistic assumptions about a monolithic medical profession speaking with one voice. As Claire Brock has argued in her analysis of the Lancet’s coverage of the woman doctor question between the 1860s and 1880s, the profession’s response was not a unanimous one. There were – in her words – “fluctuations and inconsistencies” in the journal’s response. These vacillations exist across the range of nineteenth-century medical journals, at times making it impossible even to divide them into pro- or anti-woman doctor camps.

There are, of course, journals which were vociferous in their opinions. In 1870, the BMJ ran a rather histrionic lead article in which it suggested that women entering the world of work – including medicine – would be detrimental to both the interests of their sex and society. Branding the “lady-doctor” a “traitress to her sex”, it insisted a civilised society should see women dependent on men, rather than following their own “eccentric longing[s] for the will-o’-the-wisp pleasures of independence” (2 April 1870). Meanwhile, the rather more progressive Medical Mirror defined itself against the positions adopted by most of its contemporaries, specifically deriding the BMJ for its “medieval notions concerning woman” (1 December 1869).

However, there were nuances within these journals’ editorial opinions. For instance, while the Medical Mirror felt that “in the diseases peculiar to women and children a lady physician is in her proper usefulness”, it also had some reservations about her capacity in other fields, considering it “undeniable” that a woman’s “acute sensibilities” might hinder her “from shining in the operating theatre or in the accident wards of public hospitals” (1 May 1866). The Lancet similarly believed that women and children’s medicine was “the most appropriate field” for female doctors (12 March 1870), but two months later refused to cede even this territory, suggesting women would not countenance other women as their doctors since “women hate one another, often at first sight, with a rancour of which men can form only a faint conception” (7 May 1870). Meanwhile, the Medical Press and Circular adopted a more moderate stance, arguing that – in the spirit of “toleration” – women should be allowed to pursue medical education, simultaneously doubting whether they would ever succeed (16 and 23 February 1870).

While leading articles act as something of a barometer of a journal’s editorial opinion, they cannot be taken out of context, for a multiplicity of voices exist not simply throughout a journal’s print run, but often in the same volume or issue. For instance, two weeks after its lead article querying whether there was any appetite for medical women, the Lancet printed a list of petitions (submitted by Mrs Henry Kingsley) in favour of medical education for women (21 May 1870). Indeed, many of the medical journals printed correspondence contrary to their own editorial views, allowing opponents from both sides of the debate to trade linguistic blows. Interestingly, the Medical Press and Circular did so for several weeks before wading in and issuing its own edict on the medical woman question. This indicates the importance of the correspondence pages in the journals, illustrating how readers were not merely reactive but played vital roles in generating and shaping debates.

By tracking the woman doctor debates through different issues and volumes, I have also been able to see how journals revised their opinions over time. By the 1890s, for instance, the once-paternalistic BMJ was suggesting that “[w]e have all become accustomed to what at first was a somewhat startling novelty” (17 February 1894). In the same decade, the Medical Press and Circular criticised the arguments put forward against female practitioners during debates at the Royal College of Surgeons of England and the Royal College of Physicians of London, both of which voted to continue excluding women (albeit by narrow majorities). Although it was still hesitant about whether women were physically and mentally fit for medical practice, the journal lambasted the women’s detractors as basing their arguments on “sordid, commercial ground” (i.e. a reluctance to accept competitors in the medical marketplace) (20 November 1895).

Monitoring contemporary criticism of medical news and events also allows us to gain a wider picture of professional opinion at the time. For example, in isolation, the fact that both Royal Colleges in England voted against admitting women in the 1890s might lead one to conclude that the male medical profession was still remarkably hostile towards women doctors at the turn of the century. However, the journals' coverage of the Colleges’ debates muddies the waters. Firstly, it illustrates the multiplicity of opinions that existed within the professional bodies at the time, recording the views aired by more progressive and sympathetic members. By emphasising how lively the debates were (and just how close-run the voting was) the journals wonderfully convey the precariousness of the decisions made, how tenuous the old order's hold was during this time.

Lastly, it should be highlight that among the many 'voices' we hear in the medical journals – in their transactions of debates, correspondence pages, and articles – are those of early women doctors and female medical students. Reading the BMJ’s coverage of the British Medical Association’s “Extraordinary General Meeting” in which the admission of women was debated, I particularly enjoyed Elizabeth Garrett Anderson’s apparently wry remark that the wording of the motion should be revised, given that they have already a female member: her (30 July 1892). Female doctors and laywomen (including doctors’ wives) write in to weigh in on the debates, providing both their own perspectives and points of information about their own practice. For instance, Sophia Jex-Blake writes derisively in response to one correspondent’s suggestion that women could be given poorly-remunerated midwifery cases (Lancet, 9 July 1870), while Marion Ritchie (of the Clapham Maternity Hospital) tries to deflect allegations that medical women are undercutting men for midwifery work (Lancet, 14 December 1895). Furthermore, women doctors’ writing does not appear purely in the context of debates about the medical woman movement – it also tackles clinical subject matter. Even in the years before they were admitted to the British Gynaecological Society (1901), women doctors appeared in the pages of its journal: Mrs Scharlieb – Senior Surgeon at the New Hospital for Women – contributed “Notes of Three Cases of Total Hysterectomy” in May 1896, while American doctor Mary Dixon Jones wrote on diseases of the ovary in November 1899.

The multiplicity and diversity of voices on the “medical-women question” in the pages of nineteenth-century medical journals are fascinating. Together, the cacophony of voices provides a complex picture of attitudes towards women, conceptions of medical study and practice, and professional anxieties (particularly of a pecuniary nature). While they may threaten to overwhelm, they do not undermine our ability to draw conclusions as researchers. Indeed, the wealth of material available enables us to understand how and why views were modified over time. We can begin to understand how a number of key factors – from the successes of individual pioneers such as Garrett Anderson to the perceived need for female doctors for women in India – helped to weaken hostility towards medical women between the 1860s and 1890s.

I must confess that – before commencing my current project – my engagement with medical journals had been sporadic. Like many literature students, I had turned to medical journals to ‘supplement’ my arguments and, by reading articles in isolation, had consequently been hugely reductive about the profession’s viewpoint(s). By returning to articles in their original context – looking at the way they figure in a particular issue, volume or wider print run – one begins to appreciate the value of these journals in their own right. For a researcher they are academic gold dust, showing a huge cross-section of opinion and illustrating how quickly these opinions changed over time. Most importantly, perhaps, they instill in the modern researcher a sense of how ‘live’ these debates really were for the journals’ original readers.

--Alison Moulds

Select Bibliography

Claire Brock, "The Lancet and the Campaign Against Women Doctors, 1860-1880", in (Re)creating Science in Nineteenth-Century Britain, ed. by Amanda Mordavsky Caleb (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007), pp.130-145.

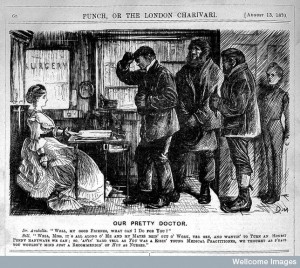

Picture credit