Sensing and Presencing Rare Plants through Contemporary Drawing Practice

Blog post contributed by Sian Bowen, Leverhulme Fellow & Reader in Fine Art at the University of Northumbria, www.sianbowen.com

https://www.youtube.com/embed/jhItil0gy1c

With support from a Leverhulme Trust Research Fellowship, I am currently developing a project, Sensing and Presencing Rare Plants through Contemporary Drawing Practice, which investigates how the materiality of drawing can make present the imperceptible nature of the vulnerabilities and resilience of rare plants. As an artist, this builds on my ongoing interest in the ways in which drawing might convey states of flux. Although I would strongly advocate that drawing can be made on any surface and in any medium, paper plays a crucial role in this project. The resulting artworks will form an exhibition which will be staged in the UK and India in 2019.

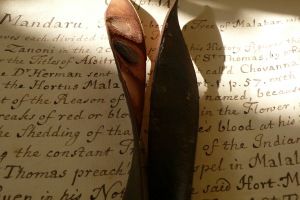

Specimens from the Druce Herbarium, Oxford Herbaria, University of Oxford.

Historically, drawing has been intrinsically connected to the collection and preservation of plants as a vehicle for scientific description and identification. With sophisticated digital visualisation technologies now occupying this central position, the project asserts that contemporary art practices, especially those concerned with themes of ephemerality - for example Anya Gallaccio’s installations of dying flowers; and Michael Landy’s print media exploration of the status of weeds - are renewing the inspirational basis of botanical illustrations and specimens.

Taking plants of Malabar as its principal concern, I aim to bring into focus - for the first time - three distinct but interconnected historical and contemporary ‘sites’ of knowledge: firstly, rare copies of the extraordinary 12-volume 17th century illustrated treatise on the flora of Malabar, and its 21st century English translation (which includes an additional commentary on the current status of the 750 plants indexed; secondly, historical herbaria in Edinburgh, Liverpool and Oxford housing fragile examples of specimens described in the aforementioned publications, and brought from India to Britain during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries; and thirdly, sacred groves surrounding temples of the tropical forests and coastal plains of Malabar, the centuries-old protection of which has ensured the survival of some of the rarest plants discussed in Hortus Malabaricus. The ways and extent to which these three sites of knowledge can shed light on the ephemeral qualities of plants and how these might be conveyed through the contemporary practice of drawing, are central to this investigation.

Specimens from the Druce Herbarium, Oxford Herbaria, University of Oxford.

I therefore arrived at the workshop, The Material Culture of Citizen Science, after having spent two days closely examining plants specimens held in the historical Indian collections of Oxford Herbaria - housed in the Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford. The role that paper plays in these collections is intriguing. The fragile, preserved plant specimens are mounted on paper that is sometimes contemporary to the period of their collection. Fine paper strips hold the specimens in place. Onto the backing papers is a palimpsest of handwritten notes and labels. Names of plants have been carefully written down, crossed out and re-named at different points in time as different systems of classification evolved or new knowledge was gained. The 17th century notebooks of collector William Sherard not only reveal information repeatedly added and discounted, but also their very covers have been made from plant-drying papers – evident in certain lights from subtle imprints. During my visit it was also possible to see copies of a complete 12-volume set of Hortus Malabaricus, with its truly remarkable botanical engravings.

Specimens from the Druce Herbarium, Oxford Herbaria, University of Oxford.

The focus of the workshop on material culture and paper technologies, gave me a valuable opportunity to re-consider the relationships between drawing, plants, paper and materiality. Plants, historically, have been a “currency” of empires, their collection and distribution having had huge economic, social, cultural and political implications – whilst paper after all, is made from material of the plant world; cotton and flax seed heads picked from across America, bark stripped from branches of the kozo and mistumata trees in Japan, and pulp made from trunks of conifers felled in Scandinavia. The wonderful range of presentations across various disciplines really brought home the potential that paper has to propose concepts and mediate ideas. This was demonstrated for example by the handwritten instructions in notebooks for medicinal recipes, the information gathered on forms for the Prussian consensus and the engravings of shells by the Lister sisters. In such cases the paper was originally selected to perform a function – a carrier of information. However the material nature of these objects offers further possibilities for interpretation and adds layers of meaning.

The presentation on Dr Auzoux’s papier-mâché anatomical models demonstrated the potential that paper has to be transformed in extraordinary ways. Fascinated as I am by the palimpsest of the labelling of herbaria specimens, I am also intrigued how a flat sheet of paper can become something ‘other’. I want to understand more fully not only ways in which paper can been transformed but also in how it can be a transformative vehicle for ideas. The very fabric of paper is, as I’ve mentioned, taken from the plant world. It seems that the new art works could harness certain characteristics connected to plant life – such as its response to light in terms of bleaching and photosynthesis and its ability to produce fugitive dyes. I plan to place an emphasis on drawing as a physical and material phenomenon that can generate new knowledge, as opposed to drawing as information gathering through marks made on a substrate. These considerations will I believe, enrich my lines of enquiry which will focus on encounters with rare plants in darkened herbaria and light-filled sacred groves and the sensory differences between their live and preserved states.

Sian Bowen installing her her drawings at Wallington Hall, Northumberland.